February 2011

Our church’s youth ministry is planning on sending some of the kids on a trip to see the Pope at World Youth Day in Barcelona, Spain. The organizers are looking to host a dinner dance to help raise funds to make that happen. As part of the program they are looking for donations of food, decorations, DJ services – the whole shebang.

And, donations of items to enter into a silent auction, with the proceeds going to help the fund grow.

I’m sure they’ll end up with the basics – items to put into themed baskets (A night at the movies, a day at the spa…), golf outings at local courses, services from parishioner’s businesses… the works. You knew I couldn’t let this opportunity pass…

So, I set to work on building a Bible box for the auction – someplace for the family to put the good book, a set of rosary beads, palms from Palm Sunday and other items. I built the sides from a set of sapele boards I had first laid out and mitered for a project that went terribly wrong. Yes, these boards were supposed to be the twin box to the one that went south.

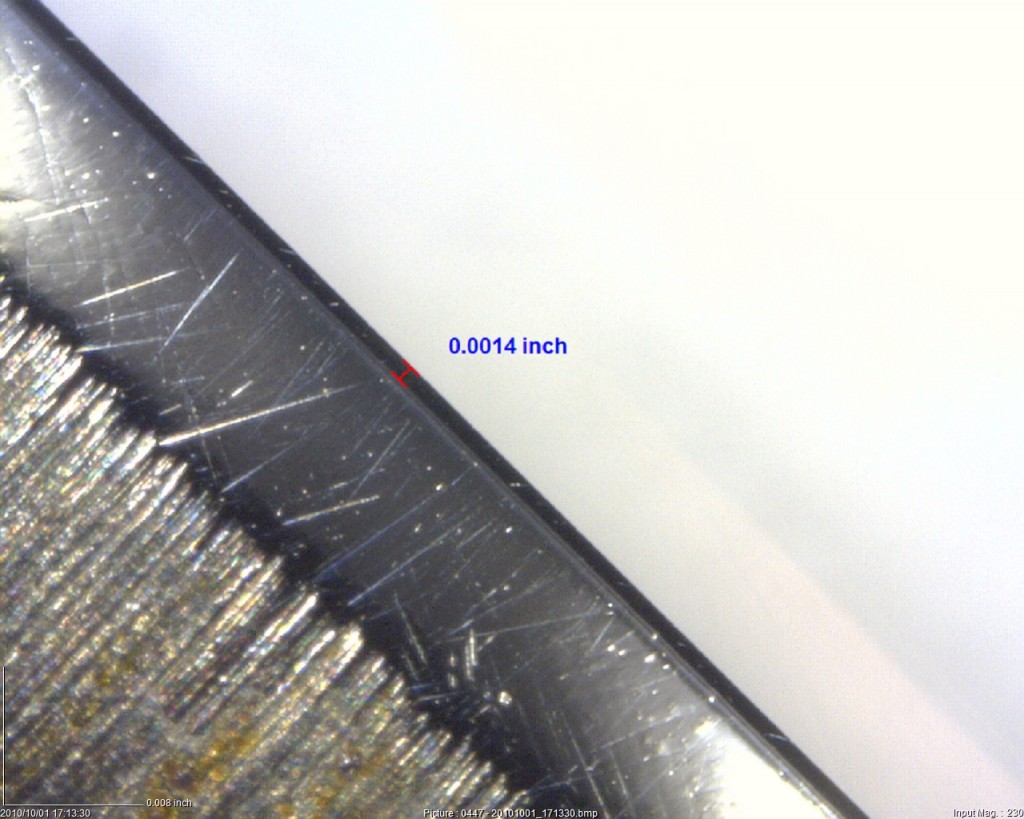

I cut and planed the box top and bottom from wider sapele pieces and fit them into dadoes to form the lid and the bottom, and then glued the mitered box together. I then cut the lid of the box free at the table saw. This was a delicate operation – you don’t want to cut all the way through on the passes. The key is to leave a little ‘web’ of wood at the top of the cut, and once all of the cuts are made, slice the box lid free with a utility knife. This way, the lid won’t get free and ruin the cut.

As I laid out the cuts with my Kehoe Jig to reinforce the corners, doubts started to enter my mind. How would this box look different than all the others I was building as of late? They all seemed to have three our four splines in them down the side, no feet, lift off lids … No, I had to do a couple of things to make this box stand out.

I started with some pieces of bird’s eye maple that had been sitting around for a few months. I planed them down to about 3/8″ thick when I built the last project with them months ago, but I can’t remember why…

I then cut some pieces of the maple into quarters and glued them onto the lid to create the shape of a cross. Once it was glued into place, I brought out the random orbit sander and brought it even with the ‘rim’ of the top. The cross shows up as a ‘negative’ relief … I think it looks cool.

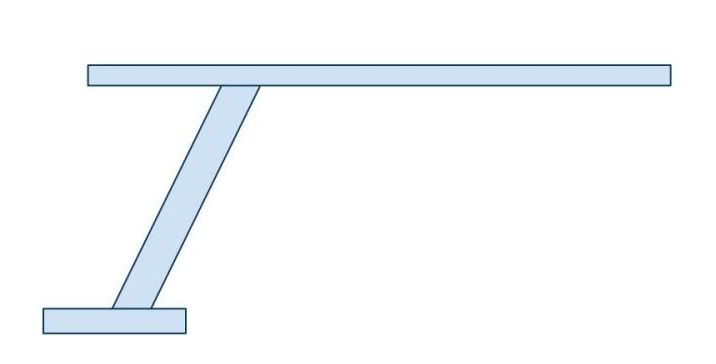

Then, I ripped a section of maple to about three inches wide. I then bevel ripped the board down the middle at 45 degrees and cut the pieces so they would come together as a mitered assembly. A quick cut at the band saw left me with ‘outside’ edges that curved up and down to form smaller feet, and I left the tops a little longer than the height of the box body to reference the top. A little bit of liquid hide glue allowed me to rub the joint together and have it hold while drying. I love that trick.

Once the glue dried, I then glued them to the outside of the box and held them in place with a band clamp wrapped around the outside.

Since the lid’s corners weren’t secured, I figured what the heck, and I threw some Kehoe splines into it. I kept them maple to continue with the contrasting wood theme.

The finish is my typical formula – a 1# cut of dewaxed shellac, followed by a thorough sanding with 320 grit paper and two coats of Watco Danish Oil. Once it was all done, I dropped it off at the church. I went to one of the ladies who was helping with my sons’ religious ed classes and told her it was for the auction. I have this feeling it may not make it to the auction – someone on the staff may buy it!

The most difficult thing about this project happened during construction. A good friend of mine looked at it on the bench and said, “Funny, it looks like the Holy Humidor.” From that moment on, all I could do was think about lining the box with cedar and putting a few stogies in it!