Even though many people laugh when I say it, I really do like music from the 1970s. For a kid coming of age during the 1980s, this is a huge leap, as many of my friends referred to the 1970s as an error instead of an era.

Sure, there were no Beatles, but the individual members were cranking out some good music. The Rolling Stones, the Who and Led Zeppelin had moved from their deep 1960’s music into a snappier sound. Funk was really coming into its own and – yes – I’ve discovered that disco revolves around frenetic bass grooves. Which I’m trying to learn. But my blasted fingers are still too fat to hit all of the notes.

One of the acts from that era I have come to appreciate is Rod Stewart. Yes, at the time, he was Rod the Bod who made the ladies swoon, but, as time has passed, I’ve come to appreciate the way he composed his music and soulful lyrics. The album that put him on the map as an artist was his 1971 work Every Picture Tells a Story. The offerings ran the gamut from a re recording of Elvis Presley’s That’s Alright Mama to the lyrical Maggie May. My favorite song on the album is the rocking title track, Every Stick it Tells a Story, Don’t it?

You heard me right. For the first dozen years or so after I first heard the song, this is how what I understood the lyrics to be. Hey, mistaking lyrics is an easy thing to do… in fact, there are plenty of songs that are misunderstood.

Now that I think about it, perhaps those misunderstood lyrics do mean something to me as a woodworker. I’ve discovered during this cabinet job with my friend Paul that relying on a tape measure to do all of your measuring can lead to inaccuracies that translate to miscut boards. It’s surprisingly easy to measure a piece at 9 7/16 inches and come back from the saw with a piece that measures 7 9/16 inches. Or 8 7/16 inches.

When you really need to be precise, you can buy a more accurate tape measure or a stainless laser-engraved rule…

But, I bet you can find the most accurate measuring tool sitting right in your scrap bucket.

Yes, I’m talking about a story stick.

Just what the heck is this magical story stick, and how does it work? Gosh, it’s the easiest thing to use. When you look at any woodworking project, there are two kinds of measurements. Nominal and actual. The nominal measurement is what the piece is supposed to measure. If you are working from a plan, and the plans say a face frame rail should be 24 inches long, well, it should be, right?

Then, there’s the real world. Maybe your saw was just a bit off. Maybe you had to plane a little extra to get rid of some machining marks. Maybe you accidentally cut with the kerf on the wrong side of the blade. Hey, stuff happens. Remember, it’s not a mistake, but a design feature…

So, if you have to fit a drawer box which has to be a very specific into this less than perfect opening, how are you going to be sure you hit the exact mark to allow enough room for the drawer slides and face frame, if you are building with one?

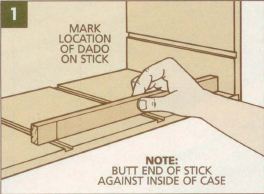

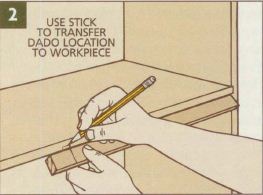

What you can do is get a piece of inexpensive wood or strip of plywood from the scrap pile. I’ve found that lighter colored species make it easier to read your marks. You just have to take this strip of wood, push it against the back of the cabinet and mark where the piece intersects the outside of the cabinet. You just accurately measured the cabinet box’s depth. Lay the stick across the front of the cabinet box, and mark the width. That’s it. No squinting to see where the cabinet’s width falls on the ruler. No deciding if you need to cut a piece strong a millimeter or 16th of an inch. The measurement is what it is.

When you get back to the shop, building couldn’t be any easier. For this project, I built the drawer boxes to be 21 inches deep. I knew this would fit into the depth of the cabinet because, yes, I had measured the depth with the story stick and it fit in the marked space.

I was using a rabbet and dado joint for the fronts and backs of the drawers. I knew I had to leave 1 inch of space free to fit the drawer into the space with the slides, and I was going to cut the depth of the rabbet at 3/8 of an inch, so by subtracting 1 3/4″ (1″ for the drawer space and 3/8″ x 2 for the length of the depth of the rabbet on both sides), I had my drawer width nailed. I subtracted this distance from the drawer opening width, set the stop on the miter gauge on my table saw and bingo, I was off to the races.

This system also works well for complex projects that would require a notepad full of measurements and notations. Instead of advanced calculus and an arcane measurement system, just a few sticks with the appropriate marks taken directly from the project’s dimensions would make your work so much easier.

Last December, when we had our kitchen counter tops replaced, the guy who came out to measure used only 20 or so strips of plywood, a hot glue gun and a pencil to get the dimensions he needed for fabrication. Two weeks later, the installers moved the pieces in and laid them down perfectly on the first try.

That is the power of the story stick, and you’ll feel like a rock star once you learn all it can do for you!