So, on this project I’m building, I have a shelf that will hold a special memento But, the shelf isn’t only to hold this item, I also need it to help hold the final piece – together with the breadboard ends – flat in an area of the building where it goes that is right by an exterior door. My concern is that with the opening and closing, there will be tremendous fluctuations in humidity, possibly making this piece warp without support.

Plus, since this is a cross-grain situation, I didn’t want to lock the shelf in place, possibly leading to cracks.

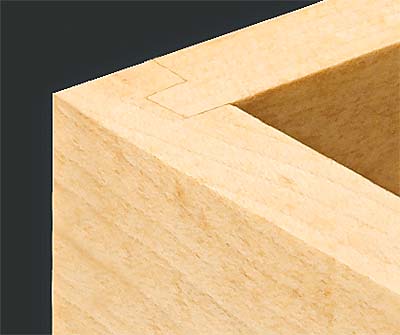

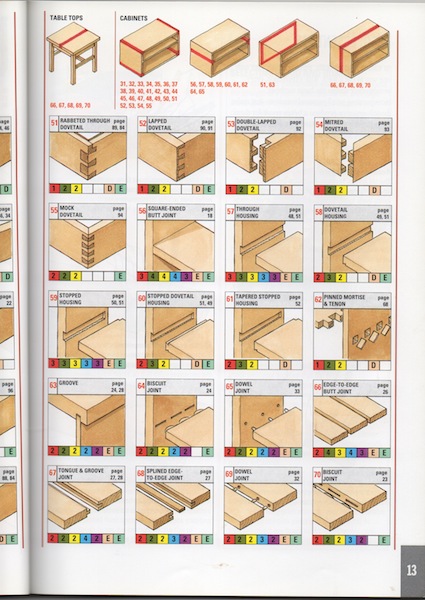

The best option I can see is to use is a sliding dovetail joint.

The sliding dovetail. It’s a member of the dovetail family that often gets overlooked. And, that’s a shame, because it’s a great joint, giving lots of flexibility. The only problem is that it can be very fussy to cut.

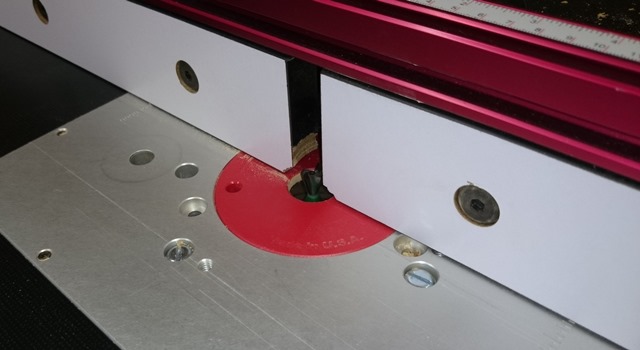

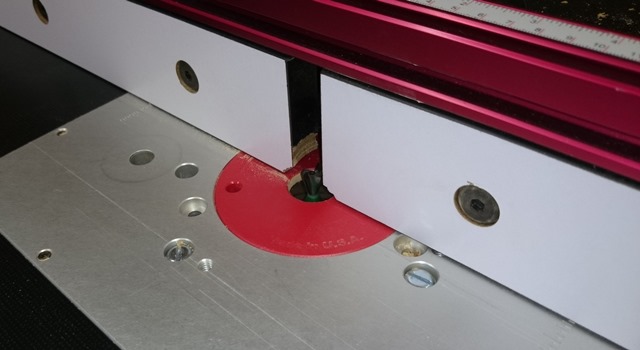

This is the method I used, and it worked well for me. The whole joint revolves around a standard dovetail bit. The total angle of the sides really isn’t important. I am using one with a 14 degree slope. This method requires a router table to make it work well,.

Once I put the bit into the collet, I lowered it into place – about one third to one half the thickness of the board I was working on.

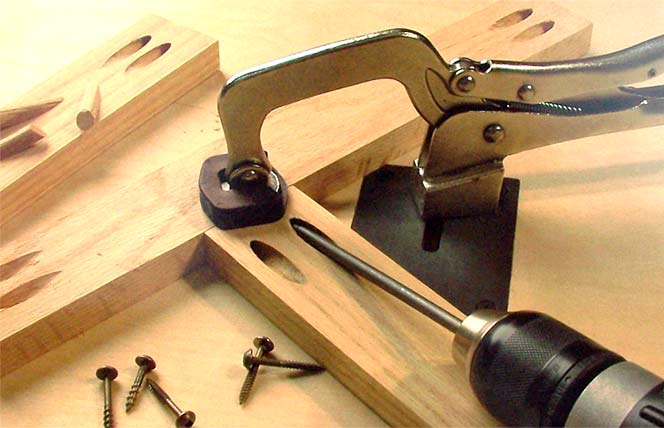

To ensure the piece wouldn’t move on me when I routed it, I used my Osborne EB-3 miter gauge from my table saw. It has a nice wide fence, covered in sandpaper to ensure a great grip.

Before you just go and push the work through willy-nilly, do yourself a favor. Cut some kind of relief groove where you plan on plowing this dovetail shaped dado. This will remove a chunk of the waste, helping your dovetail but cut more effectively. Some people will swap router bits to do this; I just ran to the table saw and cut a pair of saw kerfs.

OK, back to the router table. with a careful push through the bit – ensuring that the work is held tightly against the fence. Believe me, the spinning bit will want to make your work move.

After you push the work through the bit, flip the board over and take a look. Odds are pretty good that the dado will be packed with sawdust. That’s normal. Remember, the bit cuts wider at the bottom of the cut than at the surface of the board. Once you vacuum the chips out of the dado, it’s all good.

Now, if you would like to waste shop time and pull most of your hair out, feel free to mess with the height of the bit at this point. If this is how you have fun in your shop, be sure to seek professional help. If you would rather just build, then don’t touch the bit height. At all. You have it set perfectly.

Now, you have to get your fence ready. WITHOUT TOUCHING THE HEIGHT OF THE BIT (did I mention this before?), put the fence on your router table and bury most of the bit behind the face of the fence. This part of the joint is trial and error, and it’s very easy to make errors. Believe me.

With the majority of the bit behind the face of the fence, put the mating piece edge down, riding along the face of the fence. Now is also a great time to break out your featherboard to ensure that the piece is pressed tightly to the fence as you push it past.

Now, push the board through, then flip it over and rout the second side. This will give you the proper profile for the joint. It’s during this time that I subscribe to the mantra that it’s easier to take more wood off the joint than to add it back. Your first pass will probably leave your mating piece too wide to fit. Adjust our fence backwards by very small increments and test fit. Remember, since you are removing material from both sides of the joint, you are doubling the corrections you make.

You will know when the joint fits perfectly when the mating piece slides into the groove and goes about 2/3 the way into the groove before it binds up. There is a lot of friction working on this joint, so you will probably need to tap it into place with a mallet to get it to seat all the way in.

The fun thing about this joint is what you can do with it. If you want to affix it permanently into place, put a dab of glue at the outside edge of the joint. This way, that section will stick fast, while the rest of the joint can slide freely as the board expands and contracts with changes in humidity.

Or, if you are feeling froggy and you want your joint to be able to be disassembled, try a little wax on the joint. This way, when you are ready to knock the piece down, it will take just a few taps with a mallet to free the joint. I have seen this on bookshelves, and it’s the handiest portable design.

Sure, it takes a little it of practice, but once you try the joint, I think you will be happy with the results, and you will want to use it more often than you think you will.