Prediction is very difficult, especially if it’s about the future. – Niels Bohr

Ahh, who can forget the heady days of late 1999? The dire predictions of mass hysteria as computer systems crashed around the world. Cults foreseeing the end of civilization and the beginning of the ‘end times.’ Economists hedging their bets on an economic collapse the world hadn’t seen since the Great Depression.

Ahh, who can forget the heady days of late 1999? The dire predictions of mass hysteria as computer systems crashed around the world. Cults foreseeing the end of civilization and the beginning of the ‘end times.’ Economists hedging their bets on an economic collapse the world hadn’t seen since the Great Depression.

Imagine everyone’s relief when January 1, 2000 rolled around and the world didn’t go into the tank.

If you think the people in the late 1990’s were the first to make predictions of what the new millennium was going to look like, you’d be wrong. People have always looked ahead, based on their observations, and tried to foresee just what the future would be like.

I recently came across a .PDF of an article written in a 1950 edition of Popular Mechanics called Miracles You Will See in the Next 50 Years. Wow. This was some real Buck Rodgers kinda stuff. Rocket planes that scoot people across country in less that two hours. Shopping by video phone. Solar energy providing cheap, reliable electricity. A veritable bonanza of clean, efficient life in a technological wonderland…

I recently came across a .PDF of an article written in a 1950 edition of Popular Mechanics called Miracles You Will See in the Next 50 Years. Wow. This was some real Buck Rodgers kinda stuff. Rocket planes that scoot people across country in less that two hours. Shopping by video phone. Solar energy providing cheap, reliable electricity. A veritable bonanza of clean, efficient life in a technological wonderland…

Who am I kidding? The description of life in the year 2000 sounded soulless, sterile and – in many ways – frightening. Here are some of the predictions that made me stop and say, “huh?”

- Cooking as an art is only a memory in the minds of old people. A few die-hards still broil a chicken or roast a leg of lamb, but the experts have developed ways of deep-freezing partially baked cuts of meat.

- There are no dish-washing machines, for example, because dishes are thrown away after they have been used once, or rather put into a sink where they are dissolved by superheated water.

- Discarded paper table ‘linen’ and rayon underwear are bought by chemical factories to be converted into candy. Yuck.

Doesn’t sound like a place where anything is too terribly permanent or personal. That carries through to the home and furniture as well:

- Though (the house) is galeproof and weathterproof, it is built to last only about 25 years. Nobody in 2000 sees any sense in building a house that will last a century.

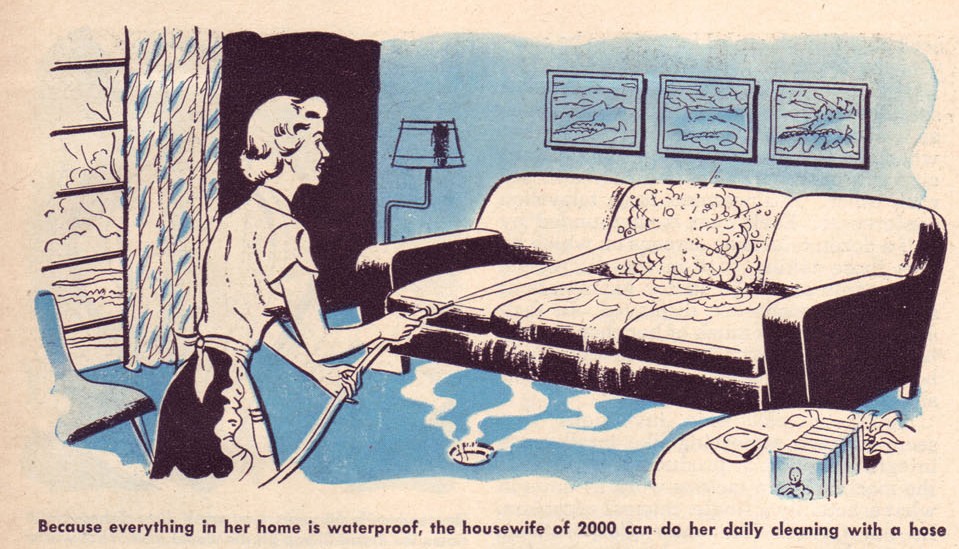

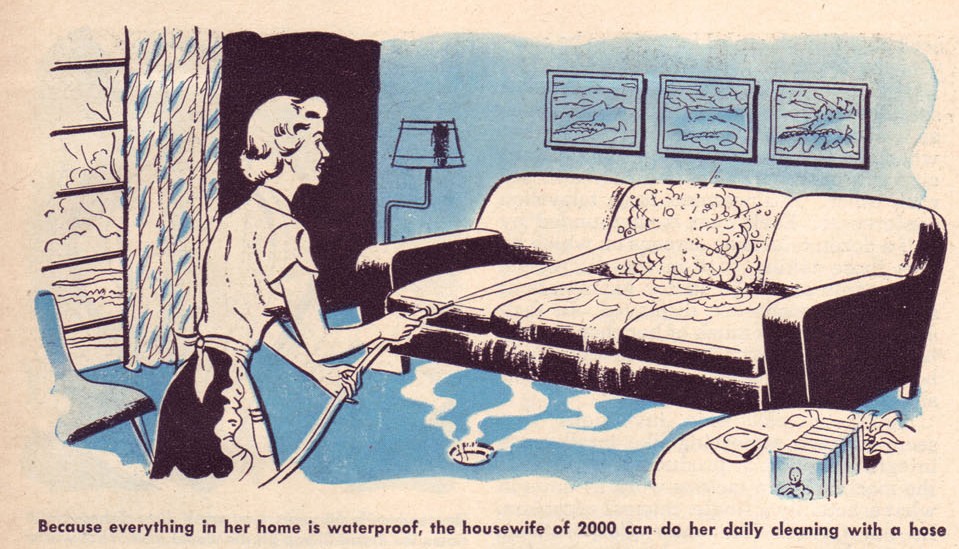

Later in the article, we see a cheery Mrs. Dobson hosing out the inside of her home – furniture included -to get that nasty dirt and ground-in grime out. The water and detergent disappear into the main central drain, a blast of hot air dries everything and the home is once again sparkling new.

Later in the article, we see a cheery Mrs. Dobson hosing out the inside of her home – furniture included -to get that nasty dirt and ground-in grime out. The water and detergent disappear into the main central drain, a blast of hot air dries everything and the home is once again sparkling new.

Of course, none of these predictions have come to pass. However, in the 1950’s, we were sure that science would solve all of our problems. Plastics, mass production and advances in technology were supposed to eliminate all of the toil and hard work from our daily lives.

If that’s the case, why did woodworking survive, and why is it a thriving hobby for hundreds of thousands?

It turns out that we can find a historical analog. In the late 1800’s, the Industrial Revolution was changing the landscape everywhere. Mass production of everything was becoming the norm, and that included furniture. Factories could spit out ornate spindles and table legs at alarmingly fast rates, catering to the Victorian fashion sense of the day. Layers of ornamentation could hide shoddy or underbuilt joinery.

But, there were those who didn’t want to go along with the mechanized flow. In England and the United States, such notables as William Morris, Gustav Stickley and Edwin Lutyens were driving furniture design into a more craft, hand made aesthetic. Even though they used machinery for some tasks, the furniture spoke boldly to strong lines and the skill of the craftsman. Frilly ornamentation was abandoned nearly altogether in the Arts and Crafts movement, with the new style playing on exposed joinery as a design element.

England and the United States, such notables as William Morris, Gustav Stickley and Edwin Lutyens were driving furniture design into a more craft, hand made aesthetic. Even though they used machinery for some tasks, the furniture spoke boldly to strong lines and the skill of the craftsman. Frilly ornamentation was abandoned nearly altogether in the Arts and Crafts movement, with the new style playing on exposed joinery as a design element.

These pioneers saw a different future than was being offered, and, today, their work is prized for its clean lines and bold showcasing of structure.

In the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, there was a similar renaissance in woodworking. The counter culture movement was rejecting all things technological, and some very creative minds, such as Sam Maloof, James Krenov, Tage Frid , George Nakashima, Wharton Esherick and Art Carpenter came into their own. Magazines such as Fine Woodworking encouraged the average homeowner to try his or her hand in this time-honored craft.

This handbuilt school of design brought with it increased innovation to allow the inexperienced craftsperson to build custom furniture. David Keller perfecting the first through dovetail jig. Delta pushing innovation in table saws. The adaptation of new industrial joinery technology into the home workshop with such items as the biscuit jointer, pocket hole jigs and the Domino.

This handbuilt school of design brought with it increased innovation to allow the inexperienced craftsperson to build custom furniture. David Keller perfecting the first through dovetail jig. Delta pushing innovation in table saws. The adaptation of new industrial joinery technology into the home workshop with such items as the biscuit jointer, pocket hole jigs and the Domino.

Not all of these innovations had shown themselves in high-tech tools. Companies such as Stanley and Record, who used to make the hand tools craftsmen relied on, were replaced by forward-thinking outfits such as Veritas and Lie Nielsen. The hand tools built there are, in many cases, an evolutionary leap above the old styles, and will serve their owners for generations to come.

This new rise of woodworking timed perfectly with the advent of the Internet. Today, many techniques, tools and materials are just a click away, and dozens of lively woodworking forums allow a free exchange of information to even the most far-away places.

So, technology has definitely provided a miracle of some sorts, even if it wasn’t exactly as envisioned back in the 1950.

It’s just a box inside a box. So, why is building drawers such an unnerving challenge for beginner woodworkers?

It’s just a box inside a box. So, why is building drawers such an unnerving challenge for beginner woodworkers?

All woodworking is a matter of scale. Some woodworkers build in huge dimensions – entire libraries of bookshelves, complete room paneling systems and kitchens full of cabinets. Others work on the small side – boxes, clocks and other small items such as toys.

All woodworking is a matter of scale. Some woodworkers build in huge dimensions – entire libraries of bookshelves, complete room paneling systems and kitchens full of cabinets. Others work on the small side – boxes, clocks and other small items such as toys. Doug has his father to thank for his woodworking roots. “My earliest

Doug has his father to thank for his woodworking roots. “My earliest Doug has built a number of outstanding larger pieces, but his work with the smaller boxes is his calling card. His boxes are seen universally as creative, innovative and drop-dead gorgeous. While these masterpieces may seem beyond the abilities of an average home woodworker, they can serve as an excellent starting point for acquiring new skills and breaking out from beyond the norm. “Making boxes takes so little material, and so little space compared with larger work. You can learn so much from them. Nearly every technique associated with larger work can be learned through making boxes. You can more easily take risks in design making a box, so you get to be more experimental. When you make a box, you don’t have to think of the whole room setting the piece will compliment or dominate.”

Doug has built a number of outstanding larger pieces, but his work with the smaller boxes is his calling card. His boxes are seen universally as creative, innovative and drop-dead gorgeous. While these masterpieces may seem beyond the abilities of an average home woodworker, they can serve as an excellent starting point for acquiring new skills and breaking out from beyond the norm. “Making boxes takes so little material, and so little space compared with larger work. You can learn so much from them. Nearly every technique associated with larger work can be learned through making boxes. You can more easily take risks in design making a box, so you get to be more experimental. When you make a box, you don’t have to think of the whole room setting the piece will compliment or dominate.” While his boxes are striking and dramatic, his preference for materials actually brings his interest closer to home. “I have a very strong preference for using Arkansas hardwoods. I seldom find Arkansas woods with very dramatic figure like you may find in exotic woods, but that is not a problem. Nearly every piece of wood is suitable for box making. If you have plain wood, you have to apply more craftsmanship to come up with something striking. And what’s wrong with that?”

While his boxes are striking and dramatic, his preference for materials actually brings his interest closer to home. “I have a very strong preference for using Arkansas hardwoods. I seldom find Arkansas woods with very dramatic figure like you may find in exotic woods, but that is not a problem. Nearly every piece of wood is suitable for box making. If you have plain wood, you have to apply more craftsmanship to come up with something striking. And what’s wrong with that?” Besides the immense satisfaction Doug takes from building these boxes and teaching the craft to thousands through his writing, he also sees the big picture what people will take from these pieces years down the road. “We each can leave an important legacy in the things we make that tell more clearly than our words about caring for each other and for the planet. In the meantime, we become more potent, more creative, and more alive when we are engaged in making things from wood.”

Besides the immense satisfaction Doug takes from building these boxes and teaching the craft to thousands through his writing, he also sees the big picture what people will take from these pieces years down the road. “We each can leave an important legacy in the things we make that tell more clearly than our words about caring for each other and for the planet. In the meantime, we become more potent, more creative, and more alive when we are engaged in making things from wood.” In much the same way, I have picked more than my share of loser tools. After woodworking for ten years, I have a collection of gadgets and gee-gaws that the inventor no doubt thought would change the face of woodworking forever. And, based on the reviews of some users, I fell hard for them, only to be terribly disappointed by their performance.

In much the same way, I have picked more than my share of loser tools. After woodworking for ten years, I have a collection of gadgets and gee-gaws that the inventor no doubt thought would change the face of woodworking forever. And, based on the reviews of some users, I fell hard for them, only to be terribly disappointed by their performance. That may be so, but I have a very different take on things.

That may be so, but I have a very different take on things. There was a wealth of knowledge there for the taking. Jim Heavey of Wood Magazine was offering a series of woodworking seminars. I watched him for about 30 minutes, and learned about six techniques I am going to add to my work. Sure, the information is out there on the Internet and in books, but I was able to stand next to him and look at how everything was set up. I could even ask questions and get immediate responses as well.

There was a wealth of knowledge there for the taking. Jim Heavey of Wood Magazine was offering a series of woodworking seminars. I watched him for about 30 minutes, and learned about six techniques I am going to add to my work. Sure, the information is out there on the Internet and in books, but I was able to stand next to him and look at how everything was set up. I could even ask questions and get immediate responses as well. If you are looking for an adhesive to stick your projects together, there are dozens of choices out there. Some you expect to see in today’s workshop (yellow carpenter’s glues). Others are prized for their specific properties such as being waterproof or extremely tough (epoxy).

If you are looking for an adhesive to stick your projects together, there are dozens of choices out there. Some you expect to see in today’s workshop (yellow carpenter’s glues). Others are prized for their specific properties such as being waterproof or extremely tough (epoxy). Ahh, who can forget the heady days of late 1999? The dire predictions of mass hysteria as computer systems crashed around the world. Cults foreseeing the end of civilization and the beginning of the ‘end times.’ Economists hedging their bets on an economic collapse the world hadn’t seen since the Great Depression.

Ahh, who can forget the heady days of late 1999? The dire predictions of mass hysteria as computer systems crashed around the world. Cults foreseeing the end of civilization and the beginning of the ‘end times.’ Economists hedging their bets on an economic collapse the world hadn’t seen since the Great Depression. I recently came across a .PDF of an article written in a 1950 edition of Popular Mechanics called

I recently came across a .PDF of an article written in a 1950 edition of Popular Mechanics called

England and the United States, such notables as William Morris, Gustav Stickley and Edwin Lutyens were driving furniture design into a more craft, hand made aesthetic. Even though they used machinery for some tasks, the furniture spoke boldly to strong lines and the skill of the craftsman. Frilly ornamentation was abandoned nearly altogether in the

England and the United States, such notables as William Morris, Gustav Stickley and Edwin Lutyens were driving furniture design into a more craft, hand made aesthetic. Even though they used machinery for some tasks, the furniture spoke boldly to strong lines and the skill of the craftsman. Frilly ornamentation was abandoned nearly altogether in the  This handbuilt school of design brought with it increased innovation to allow the inexperienced craftsperson to build custom furniture. David Keller perfecting the first through dovetail jig. Delta pushing innovation in table saws. The adaptation of new industrial joinery technology into the home workshop with such items as the biscuit jointer, pocket hole jigs and the Domino.

This handbuilt school of design brought with it increased innovation to allow the inexperienced craftsperson to build custom furniture. David Keller perfecting the first through dovetail jig. Delta pushing innovation in table saws. The adaptation of new industrial joinery technology into the home workshop with such items as the biscuit jointer, pocket hole jigs and the Domino.