I’d like to take a moment to introduce you to the tool I love to love – and hate. This is my belt sander. A Black and Decker homeowner’s model I picked up at a local Wal Mart about six years ago.

I’d like to take a moment to introduce you to the tool I love to love – and hate. This is my belt sander. A Black and Decker homeowner’s model I picked up at a local Wal Mart about six years ago.

Before I go any further, yes, I am quite aware that I advertise myself as a hand tool enthusiast. It also obviously has a tail that plugs into an outlet. Many of you are also thinking that there is no place in the fine woodworker’s shop for one of these crude instruments of sound and dust. Besides, it’s not even made by a ‘serious’ woodworking tool manufacturer.

It’s all true. This bright orange baby (by the way, I believe it might be bright orange so motorists can avoid it when it’s pitched into a road) uses some of the most diminutive belts out there – 3″ x 18″. Even it’s lousy dust bag doesn’t work any more. I used to take the time to put it on the sander, but it developed a hole near the top zipper that just blows dust straight up into the air. And, it’s a very hungry machine. I affectionately call it the belt saw, because if you leave it on the work for too long, it digs out one heck of a divot in the wood.

So, why keep it?

Even in its total nastiness, it’s another one of those shop essentials I can’t seem to do without. Just recently, I was working on my Christmas presents, I had to reach for it several times. First when I was making the end grain cutting boards.

In my last post, I alluded to the fact that my milling and gluing operations need to become a little more exacting. So, when I pulled them from the clamps, they were pretty uneven. So, I had to mosey down the street to the local Home Depot, where, much to my surprise, I discovered that Norton actually makes a line of sanding belts in that tiny size. There were three grits to choose from – 50, 80 and 120, and I bought the two packs of all three grits.

While it did take the better part of a Saturday afternoon to grind the unevenness out of the boards, I knew it was much safer than trying to run the end grain boards through the planer. With my iPod on under my hearing, breathing and eye protection, I grooved while my errors were erased totally, leaving a perfectly smooth board. No mean feat, given that end grain is very tough stuff – making it an excellent choice for end grain cutting boards!

I changed grits to the 80, then finally to the 120 for those last very light passes, leaving just enough for me to sand out with the random orbit sander.

Later, when I tried out the Kehoe jig for a set of the photo bookends, the belt sander came out again. I trimmed the dovetail splines as close to the work as I dared, and then used the belt sander to take them down flush with the board.

Are there better ways to accomplish these tasks? Sure. I could get out with a block plane and use that. But, for some reason, I seem to get better results using the belt sander for the heavy lifting and the hand tools for the fine work.

So, I’ll keep my belt sander. For now. It does what it does, but it does what it does pretty well.

But, I’m definitely keeping a wary eye on that tool!

You know you have come to a new place in your life as a woodworker when the mention of a monumental baseball decision involving wood draws you away from your morning coffee.

You know you have come to a new place in your life as a woodworker when the mention of a monumental baseball decision involving wood draws you away from your morning coffee. For MLB’s formative years, two different types of woods were used to make bats. Hickory, due to its very tough nature, and ash, due to its strength and lighter weight. Hickory became less popular through the years because it is a heavier wood. With pitchers throwing faster balls, bat speed (which is higher with a lighter bat) became a much more important trait than plain slugging power provided by a heavier bat.

For MLB’s formative years, two different types of woods were used to make bats. Hickory, due to its very tough nature, and ash, due to its strength and lighter weight. Hickory became less popular through the years because it is a heavier wood. With pitchers throwing faster balls, bat speed (which is higher with a lighter bat) became a much more important trait than plain slugging power provided by a heavier bat. The maple bats caught on like wildfire. Slugger

The maple bats caught on like wildfire. Slugger  Two serious injuries occurred at Dodger Stadium in April this year.

Two serious injuries occurred at Dodger Stadium in April this year.  This is one of those projects I have always thought about, but never got around to building. That was until I had to build a box that had mitered corners. Trying to square those slippery joints and keep the joints aligned… well, that was tough.

This is one of those projects I have always thought about, but never got around to building. That was until I had to build a box that had mitered corners. Trying to square those slippery joints and keep the joints aligned… well, that was tough. After I built this, I finished it with four coats of polyurethane to help prevent any glue from sticking to the jig.

After I built this, I finished it with four coats of polyurethane to help prevent any glue from sticking to the jig.

On the flip side, this is where the bigger clamps call home. This is where I go when I need the muscle to glue up big projects.

On the flip side, this is where the bigger clamps call home. This is where I go when I need the muscle to glue up big projects. In case you have been living under a rock, a lady by the name of Maureen McCormick recently published her memoirs.

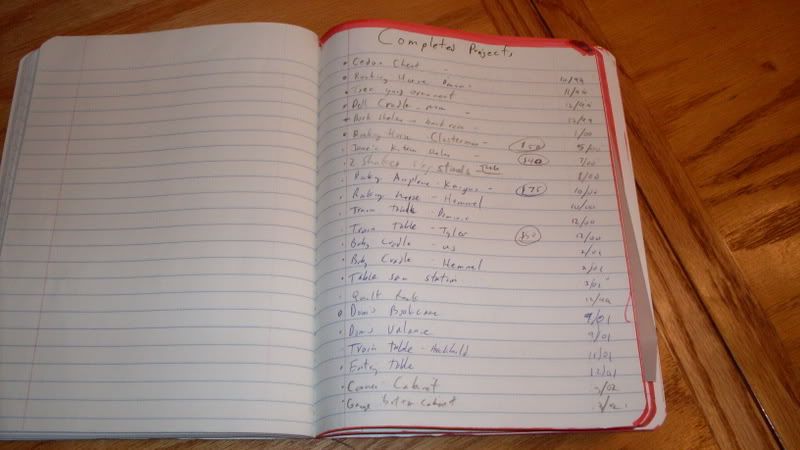

In case you have been living under a rock, a lady by the name of Maureen McCormick recently published her memoirs. However, it does – in a way – chart my woodworking progress through the years.

However, it does – in a way – chart my woodworking progress through the years. Those front pages do tell kind of a funny story about projects that never saw the light of day, designed with just unbelievably bad technique. Many of those babies really needed to be strangled in their cribs.

Those front pages do tell kind of a funny story about projects that never saw the light of day, designed with just unbelievably bad technique. Many of those babies really needed to be strangled in their cribs.