When my brothers and I were very young, our family lived upstairs in a two-family house in Ridgefield Park, New Jersey. And, if you were to check our baby albums out, you would notice that all of the upholstered furniture in the house was covered in plastic slip covers.

They were insanely uncomfortable in our un-air conditioned home during the warm summers, but they served their purpose – they kept stains off the furniture. Remember, kids like to spill stuff. And, the more brightly colored the substance, the more likely it is to be spilled and leave permanent stains.

This got me to thinking… on those occasions where I do want to change the color of a board, why do I reach for either a wood stain or aniline dye? Why not try some of those things that will stain carpets, clothing or furniture?

To see how well some of these alternate dyes work, I set up a little experiment. What stains badly if it comes into contact with household fabrics? I set up a sample board – a length of birch plywood – and lined up my candidates…

From left to right, I have Rit fabric dye – dark forest green, sugarless Kool-Aid drink mix, strong coffee my wife and I didn’t drink, an ultra cheap-yet-cheerful cabernet sauvignon and a strongly brewed batch of tea. I also used some Minwax red oak oil stain as a control.. showing just what a wood stain is supposed to look at.

What were the results? Well, here’s what I came up with (Click on the images to see larger photos):

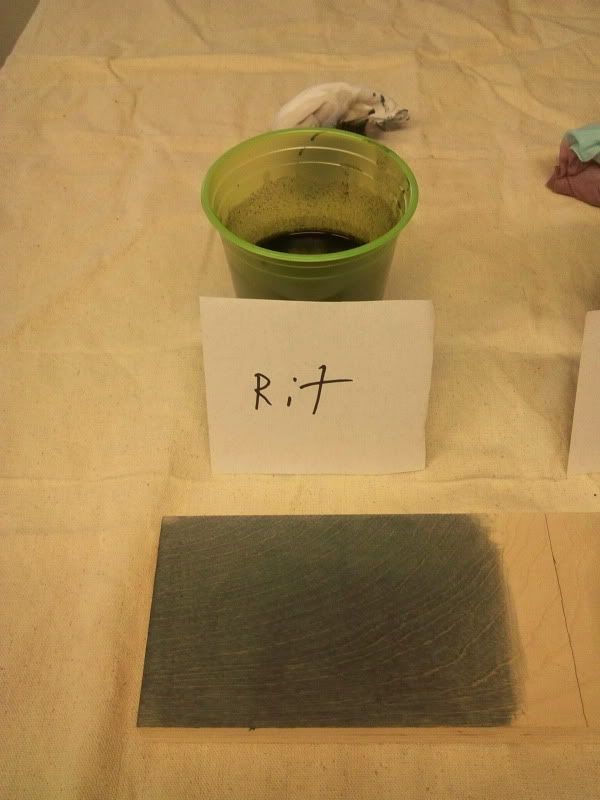

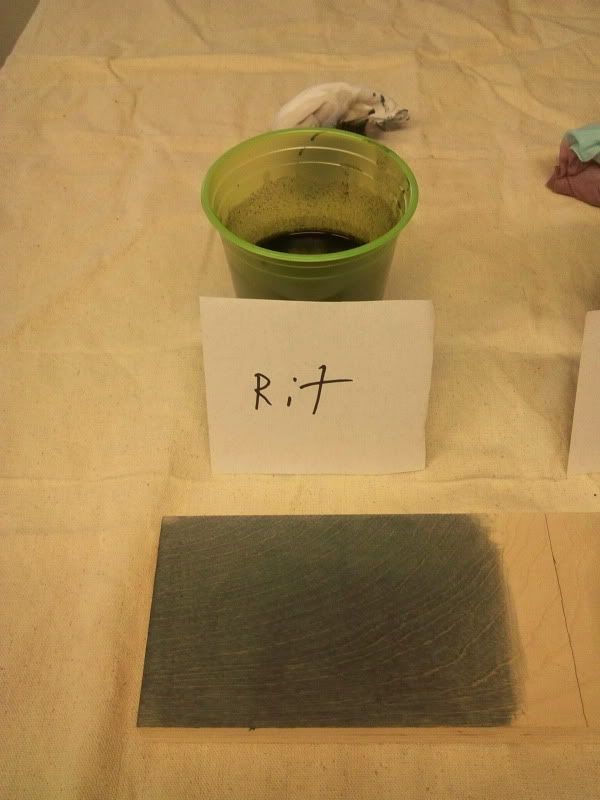

Rit dye ($1.10/package) – I mixed this popular clothing dye at the ‘strong’ ratio of one packet per cup of hot water and let it sit for a while. It gave a very dark green cast to the board on the first application, and it got even darker on the second application. While the Rit dyes aren’t typically offered in wood-tones, if you are looking to add a splash of vibrant color to a project (say for a child), this ultra-cheap yet effective dye may not be a bad choice.

Rit dye ($1.10/package) – I mixed this popular clothing dye at the ‘strong’ ratio of one packet per cup of hot water and let it sit for a while. It gave a very dark green cast to the board on the first application, and it got even darker on the second application. While the Rit dyes aren’t typically offered in wood-tones, if you are looking to add a splash of vibrant color to a project (say for a child), this ultra-cheap yet effective dye may not be a bad choice.

Kool-Aid (20¢/packet) – I mixed one package of this unsweetened kid’s drink into a cup of water (normal ratio is one packet to two quarts of water) and wiped it on. This had an interesting effect – where I wiped it on, the color was a sickly purple, but the mix that wicked away on the wood fibers appeared to be a pure blue. Ultimately, the color was a very unattractive purple and didn’t do it for me.

Kool-Aid (20¢/packet) – I mixed one package of this unsweetened kid’s drink into a cup of water (normal ratio is one packet to two quarts of water) and wiped it on. This had an interesting effect – where I wiped it on, the color was a sickly purple, but the mix that wicked away on the wood fibers appeared to be a pure blue. Ultimately, the color was a very unattractive purple and didn’t do it for me.

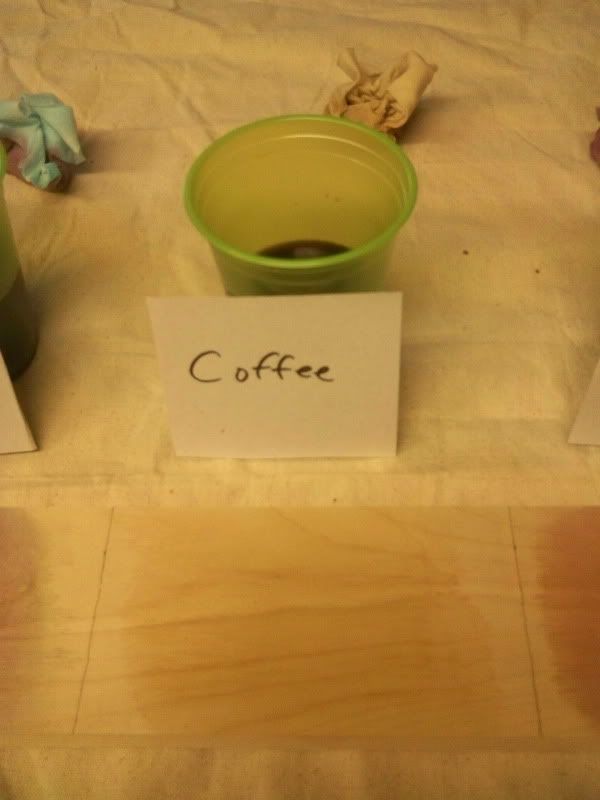

Coffee (the one pound bag cost $6.00 – we used about 35¢ for this pot) – BoyhowdydidIgettodrinkalotofcoffeetomakethishappen…. After I got over my jitters, I wiped three coats of strong black coffee on the board and I have to say was I ever unimpressed. Either it wasn’t quite strong enough, I didn’t use enough of it or coffee is a terrible wood stain. It did impart a very pale tan to the board, but it was very subtle.

Coffee (the one pound bag cost $6.00 – we used about 35¢ for this pot) – BoyhowdydidIgettodrinkalotofcoffeetomakethishappen…. After I got over my jitters, I wiped three coats of strong black coffee on the board and I have to say was I ever unimpressed. Either it wasn’t quite strong enough, I didn’t use enough of it or coffee is a terrible wood stain. It did impart a very pale tan to the board, but it was very subtle.

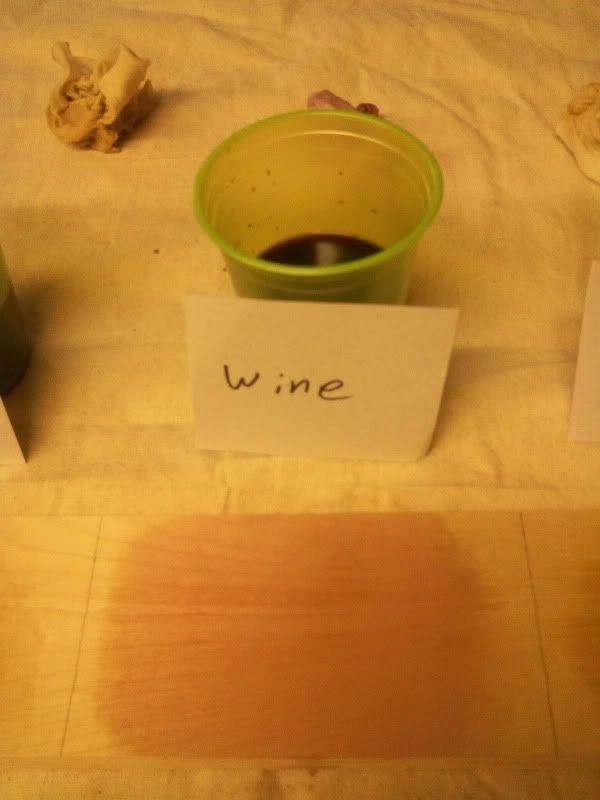

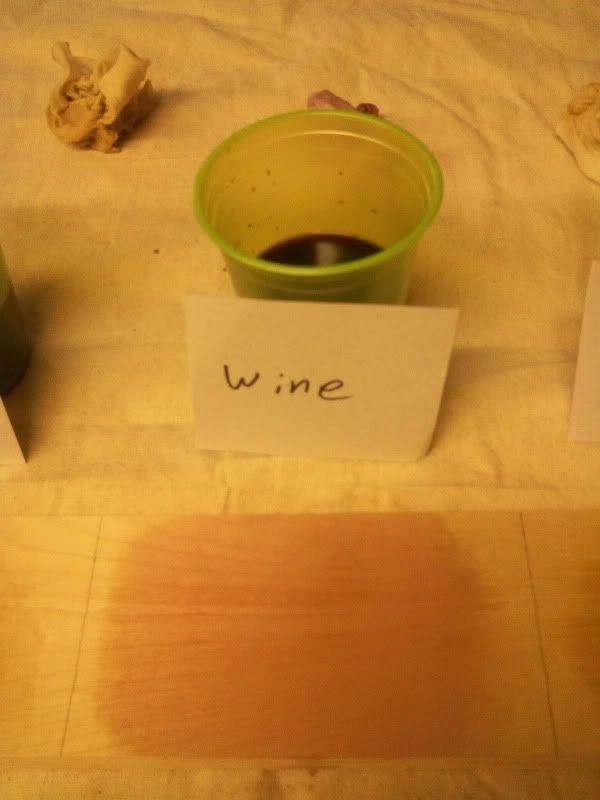

Wine ($2.95/bottle – I told you it was cheap) – In vino, veritas. And, the truth is that the wine proved to be a very interesting dye. I wanted this to work very well, but the first coat wasn’t impressive. By the time I got to the third coat, however, things changed. Cab tends toward the ruby end of the spectrum (versus a shiraz, which is more purple), and the final results were very easy on the eyes. A very pleasant look that might be suitable for accent pieces for a wine cabinet.

Wine ($2.95/bottle – I told you it was cheap) – In vino, veritas. And, the truth is that the wine proved to be a very interesting dye. I wanted this to work very well, but the first coat wasn’t impressive. By the time I got to the third coat, however, things changed. Cab tends toward the ruby end of the spectrum (versus a shiraz, which is more purple), and the final results were very easy on the eyes. A very pleasant look that might be suitable for accent pieces for a wine cabinet.

Tea ($1.15 for a box of 24 family size ice tea bags) – With all of the sickness that’s been in our house the past few weeks (colds and flu), we’ve been through a lot of tea bags. I have heard that people have used tea successfully as a dye for lighter woods, so I was looking forward to trying this. From the first (of three) coats, the tea showed it was superior to coffee and provided a warm patina, much like wood that had been allowed to age for a while after being cut and surfaced. I would certainly consider using tea for future projects.

Tea ($1.15 for a box of 24 family size ice tea bags) – With all of the sickness that’s been in our house the past few weeks (colds and flu), we’ve been through a lot of tea bags. I have heard that people have used tea successfully as a dye for lighter woods, so I was looking forward to trying this. From the first (of three) coats, the tea showed it was superior to coffee and provided a warm patina, much like wood that had been allowed to age for a while after being cut and surfaced. I would certainly consider using tea for future projects.

As was expected, the commercial Minwax stain provided a deep, rich color to the wood on the first coat with minimal fuss. Of course, there was the inevitable smell did fill the shop and the stain on the rag did color my fingers, but it was the winner hands down.

As was expected, the commercial Minwax stain provided a deep, rich color to the wood on the first coat with minimal fuss. Of course, there was the inevitable smell did fill the shop and the stain on the rag did color my fingers, but it was the winner hands down.

What did this test teach me, besides the need to use gloves when staining a project? I found that some lower cost alternatives to commercial wood dyes and stains are viable options. They can provide an interesting and unique look to your piece – whether as an accent or to set a tone for the entire project.

Oh, and I learned that all of these different items which have gotten me into trouble all of these years can be used for the power of good, instead of making your mom angry.