At my day job, I have given hundreds of hurricane and disaster preparedness talks. Big groups. Small groups. Companies, churches, neighborhood association meetings … you name it, I’ve gone there and spoken. For me, it’s all old hat now.

But, that hasn’t always been the case. When I first started out, I was told by my boss at the time that I needed to not run my talks free-form. Instead, I was encouraged to build a PowerPoint presentation, rehearse my material based on cues from what was on screen and NEVER deviate.

For my first few talks, this worked well. I never forgot a single point. I always put the emphasis on the key message I wanted to convey. I went from success to success, clutching tightly to the security blanket of my canned presentation.

Then, well, it had to happen. I went one place to talk, and blammo – no outlet was convenient for me to set up my projector and laptop, and I didn’t have access to an extension cord. Boy, did that ruffle my feathers.

The same thing happens when we are in the workshop. When we have our table saw tuned up and ready to make a cut, we become comfortable using the equipment. But, if you need to cut something on edge or try something a little out of our comfort range, it’s easy to get flustered – and worried – by the operation.

“That’s where feather boards come in,” said Dan Walter of Eagle America. “These simple jigs give you much more control – and confidence – over your operation.”

Feather boards are very useful jigs that help hold your work down to the table or against your fence to ensure a more accurate cut. And, they also can help prevent kickback, improving safety.

“The classic way to make a feather board is to fish a piece of scrap out of your wood stash, cut a series of parallel angled fingers and clamp it down to your saw,” said Dan. “And, you know, there is nothing wrong with that. It’s a cheap, practical shop solution.”

But, Dan also told me that commercial feather boards offer more versatility, are more durable and don’t take valuable shop time to make. Eagle America carries an extensive line of feather boards – each of which has special features.

“If you need feather boards for your cast iron topped table, band saw or other ferrous metal work surface, the Magswitch featherboards offer incredible convenience and flexibility.” Using a special magnet users can switch on and off, these feather boards can mount anywhere on the table, independent of the miter gauge slot.

“If you need feather boards for your cast iron topped table, band saw or other ferrous metal work surface, the Magswitch featherboards offer incredible convenience and flexibility.” Using a special magnet users can switch on and off, these feather boards can mount anywhere on the table, independent of the miter gauge slot.

Jessem’s Paralign models allow users to align them parallel to the work piece while they are clamped in the table. “In router tables, this is a very handy feature that allows you to skip all of the trial-and-error fidgeting to get the set up right.”

Jessem’s Paralign models allow users to align them parallel to the work piece while they are clamped in the table. “In router tables, this is a very handy feature that allows you to skip all of the trial-and-error fidgeting to get the set up right.”

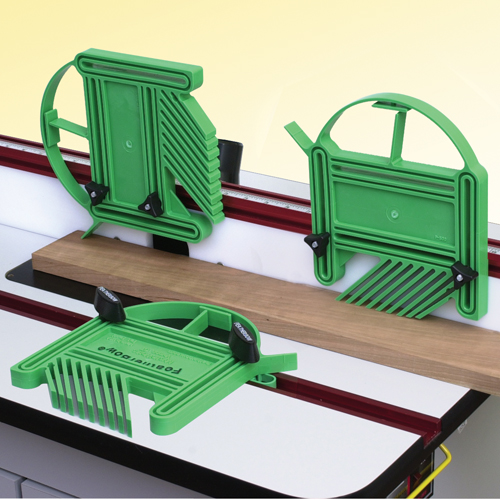

Milescraft’s dual slide motion feather boards feature large ergonomic handles for tightening them in place. “What a boon for people who may have limited hand strength. The ability to set these into place and know they will be rock solid helps ensure accuracy in cuts.”

Milescraft’s dual slide motion feather boards feature large ergonomic handles for tightening them in place. “What a boon for people who may have limited hand strength. The ability to set these into place and know they will be rock solid helps ensure accuracy in cuts.”

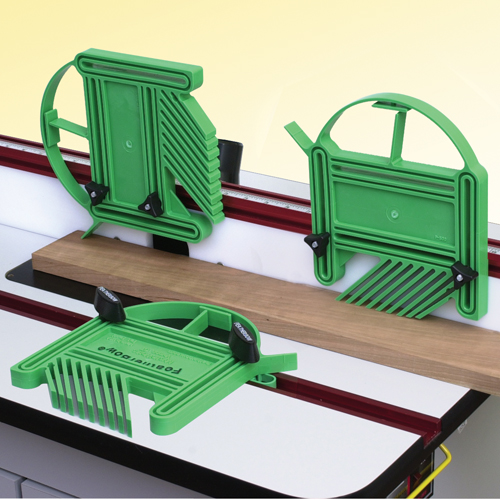

Feather Bow’s offerings feature a traditional looking feather board finger design on one side and an innovative bow hold down on the other. Shaped somewhat like the leaf spring in a car, this focuses the pressure exactly where you need it without applying it across the entire length of the fingers. “These babies work very well on router or shaper tables where it’s critical to get proper bit or cutter contact to ensure a flawless shaping job.”

Feather Bow’s offerings feature a traditional looking feather board finger design on one side and an innovative bow hold down on the other. Shaped somewhat like the leaf spring in a car, this focuses the pressure exactly where you need it without applying it across the entire length of the fingers. “These babies work very well on router or shaper tables where it’s critical to get proper bit or cutter contact to ensure a flawless shaping job.”

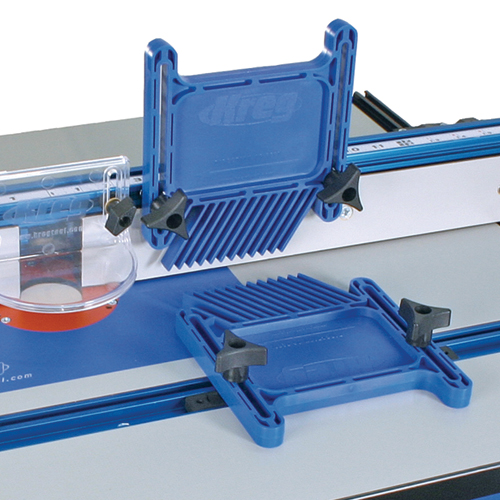

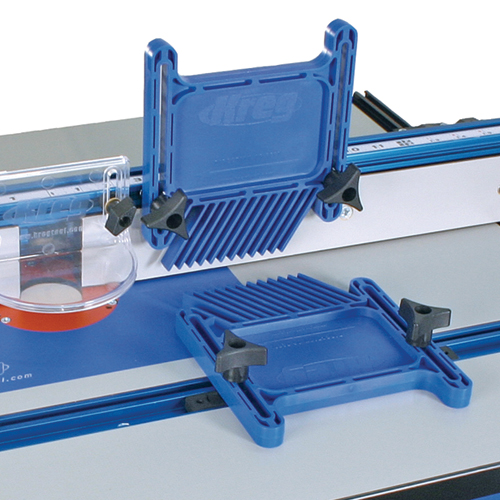

And, Kreg’s True Flex models not function as either a feather board or a stop block. “Their locking system also relies on a wedge to get a solid lock in a miter slot. That’s going to help ensure nothing slips when you are pushing the board past the blade or cutter.”

And, Kreg’s True Flex models not function as either a feather board or a stop block. “Their locking system also relies on a wedge to get a solid lock in a miter slot. That’s going to help ensure nothing slips when you are pushing the board past the blade or cutter.”

Dan also pointed out that many of these commercial feather boards can also be stacked together to give you control when resawing, cutting raised panels on a table saw or other functions. “I’m always surprised when a company comes out with a new and innovative feature on such an old power tool standby. There are some creative minds at work!”

My speech in front of that group sure threw me for a loop. But, it also taught me to look beyond just that one tool in my public speaking toolbox. Today, when I go out to talk, I know that I can adjust my presentation style to meet the needs of the specific group I’m addressing.

And, it allows me to stop obsessing over what could go wrong during the talks and start enjoying my time off in the shop a whole lot more.