I love watching football. During the NFL season, I’ll wrap up work in the shop early on a Sunday afternoon, call the kids in from the backyard, pop some popcorn, heat up some hot wings and the three of us will sit and watch a solid ten hours of games. The live drama. The hard hits. The raw emotion and energy. We cheer our fool heads off and eat all the foods we know we can’t have during the week.

In football, as in all professional sports, you start to notice that there is a sort of unwritten rule that most players follow. For example, in an after game press conference, you might see one team’s star running back or linebacker who had a career day tell the reporters, “We played a hard game against a tough team. The win was great, but there are some things we have got to work on to improve our game.” It always amazes me that you’ll hear this coming from the mouths of players or coaches – even after an impressive win. Don’t they know they just crushed the opposing team? Why doesn’t anyone ever admit to playing a perfect game?

Many woodworkers do the same thing with their projects.

I’ve done it. You’ve done it. We all have done it. Here’s an example that happens to me. After three or four months of planning, picking out lumber, cutting precision joints and buffing the final finish to a lustrous shine, my wife walks into the shop.

I’ve done it. You’ve done it. We all have done it. Here’s an example that happens to me. After three or four months of planning, picking out lumber, cutting precision joints and buffing the final finish to a lustrous shine, my wife walks into the shop.

“Oh, my goodness!” she says. “That is one impressive piece!”

“Well, honey, let me point out all of the goof ups I made. Look at this miter that didn’t close all the way, and this rail that I misglued and had to live with and this glue smudge under the finish and…”

Soon, I find myself on my hands and knees pointing out a drop of dried glue under the bottom shelf that only the dust bunnies will ever see. That’s when my wife will say something like, “Well, I think this is a very nice piece,” turn around and go back into the house as I frantically search for more major snafus lurking in my work.

Why on Earth do we do this to ourselves? Do we gain some type of masochistic joy in beating ourselves up over the slightest goof?

If you worked in an office where your boss came in after every project – even projects that win universal acclaim – and verbally flogged you for the smallest mistake, like not formatting the page footer exactly as she would have, would you stay at that job? After a while, most folks would hit the bricks, and anyone who stayed would be hard pressed to find any joy in coming to work.

Then why would you do that to yourself? Remember, in this case, you have to live with your boss every stinkin’ day.

To help regain my sanity – if I had any to start with – I had to create a new process when it came time to show my work to someone. Even though I have a list of the boo boos in my head, I’ll invite my wife into the shop and have her take a look at the finished project. I have to FORCE myself to be quiet while she takes in the piece. When she gets close to where the foul up is, I have to fight the urge to blurt out what she should be looking for as she runs her hand over the finished wood. Sometimes, I have to grab the vise handle and squeeze it while she picks up the smaller pieces and gives them a thorough once over. I sweat as she opens the doors and drawers, wondering if they are going to fall off the hinges or runners.

“I like it. Good job” Then, she leaves the shop.

I exhale hard. The tension drains. Maybe my mistakes REALLY aren’t as bad as I thought they were at first. Maybe you really do need an electron microscope to see that not-too-gappy joint that looks as big as the Grand Canyon in my eyes.

That’s when I start doing my end zone touchdown dance!

Buying a new blade can be a confusing experience. That’s why this guide from Rockler Tools is so valuable.

Buying a new blade can be a confusing experience. That’s why this guide from Rockler Tools is so valuable.

When woodworkers speak about the challenges they face, they normally mention something like cutting tight-fitting joints, selecting the proper wood and achieving a flawless finish. Now, imagine stepping up the challenge dramatically by working on a project entirely of curves, exposed to salt water and worth several million dollars.

When woodworkers speak about the challenges they face, they normally mention something like cutting tight-fitting joints, selecting the proper wood and achieving a flawless finish. Now, imagine stepping up the challenge dramatically by working on a project entirely of curves, exposed to salt water and worth several million dollars. Achieving these outstanding results takes time, patience and a lot of planning. After receiving the yacht’s unfinished hull, it is taken to the boatyard where it first has to be set perfectly level to help make the woodwork easier. Once set, measurements are taken, pencil is put to paper and the real planning work begins in earnest. It typically takes several months to arrive at a plan that is both workable and approved by the client.

Achieving these outstanding results takes time, patience and a lot of planning. After receiving the yacht’s unfinished hull, it is taken to the boatyard where it first has to be set perfectly level to help make the woodwork easier. Once set, measurements are taken, pencil is put to paper and the real planning work begins in earnest. It typically takes several months to arrive at a plan that is both workable and approved by the client. With all of these curves, two tools are essential in Francois’ arsenal. “I’d really have a difficult time working without a band saw with a 6 mm blade and my router and bit collection. They give me the control and flexibility I need.”

With all of these curves, two tools are essential in Francois’ arsenal. “I’d really have a difficult time working without a band saw with a 6 mm blade and my router and bit collection. They give me the control and flexibility I need.” You might expect the owners of these hand-crafted beauties to forget who did all of the work once the yacht is delivered, but that’s not the case. When Francois finished a yacht called Pegasus back in 2005, the owner invited him out for the first cruise. “The day it launched, we fired up the engine and went for a test run. The next day we fitted all the windscreen wipers and then went to top up the tank with diesel. Now it was time to go deep sea far out for sea trials which took about 6 hours. It was awesome to say the least.”

You might expect the owners of these hand-crafted beauties to forget who did all of the work once the yacht is delivered, but that’s not the case. When Francois finished a yacht called Pegasus back in 2005, the owner invited him out for the first cruise. “The day it launched, we fired up the engine and went for a test run. The next day we fitted all the windscreen wipers and then went to top up the tank with diesel. Now it was time to go deep sea far out for sea trials which took about 6 hours. It was awesome to say the least.”

Sure, some people laugh when you quote from Wikipedia – the Internet’s user-defined online encyclopedia.

Sure, some people laugh when you quote from Wikipedia – the Internet’s user-defined online encyclopedia. I’ve done it.

I’ve done it. Look in most woodworking shops, and, no doubt, you’ll find a pretty oddball collection of tools. Sure, there are the basics – a table saw, band saw, router, you know, the usual.

Look in most woodworking shops, and, no doubt, you’ll find a pretty oddball collection of tools. Sure, there are the basics – a table saw, band saw, router, you know, the usual. From some very humble beginnings as a woodworker (his first project was a tissue box holder for his wife back in 1995), Niki has expanded his knowledge of the craft, and has taken his ingenuity to new heights.

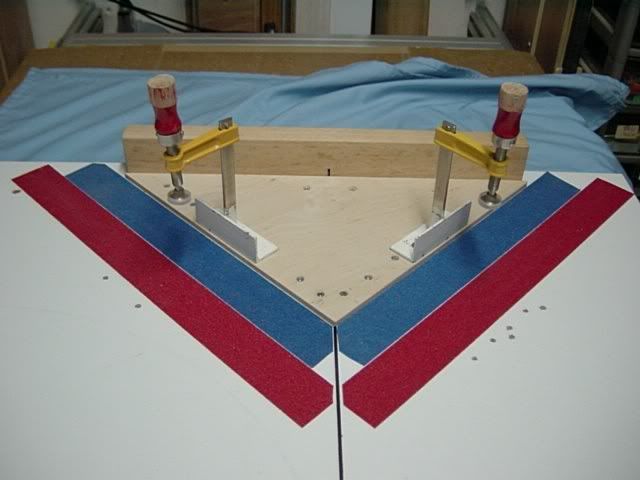

From some very humble beginnings as a woodworker (his first project was a tissue box holder for his wife back in 1995), Niki has expanded his knowledge of the craft, and has taken his ingenuity to new heights. Just as a proud parent won’t select a favorite child, Niki actually uses most of his jigs while building his projects. “What’s my favorite jig? That’s a difficult question. I think that I use all of them in almost every project because most of the steps are very repetitive. Wood preparation, cutting to dimensions, joinery, gluing etc. Because my machinery includes basic shop power tools, I think that every one of the jigs finds its place in a project.”

Just as a proud parent won’t select a favorite child, Niki actually uses most of his jigs while building his projects. “What’s my favorite jig? That’s a difficult question. I think that I use all of them in almost every project because most of the steps are very repetitive. Wood preparation, cutting to dimensions, joinery, gluing etc. Because my machinery includes basic shop power tools, I think that every one of the jigs finds its place in a project.”