Ask people how they define the word ‘recreation’, and you are bound to get wildly differing answers.

For my wife, recreation means taking a folding chair and a sun umbrella down to the beach with a cooler full of cold water and a murder mystery. She can spend hours just laying back and relaxing.

For me, well, I steer more toward the active. Case in point, I am currently coaching my son’s youth recreational basketball team.

Before I started woodworking eleven years ago, the local rec league was desperate for people to coach, so I stepped in to offer my services. That’s the last time I had coached, and our team did pretty well. Now, with my son in the 11 – 12 age group and the hurricane speaking tasks slowing down for the season, I stepped up again to take the reins.

My ten-person roster is full of kids of differing motivations, skill sets and levels of experience. My job is to whip them into a unified team. But how?

I have been watching some of the other coaches in the league to see how they do their work. I’ve seen coaches who just want to scrimmage during their practices, playing half their team against the other half. Then, I’ve seen coaches focus intently on setting up designed plays. Their players have to remember a bewildering number of play names and learn exactly what they have to do in each situation.

While both approaches have their merit, I have decided to focus heavily on the fundamental steps of playing the game. After all, I could teach them set plays, but if they understand how to move without the ball, play solid defense and rebound correctly, they can use these skills later on down the road should they continue playing.

In much the same way, I have received a number of e-mails since I started working on Tom’s Workbench from woodworkers just starting out the craft. “Tom, I’m looking to learn how to cut dovetails. Can you tell me how to get started?” “I’ve been trying to build a mission style lowboy for my wife. I’m not sure how to begin.” “My finishing is just awful. Where am I going wrong?”

I’m not going to claim that I am a woodworking expert – that I have all of the answers for every single problem or question. In fact, there are still MANY different things that I need to learn myself, and there are still dozens – if not hundreds – of aspects of woodworking I have yet to even touch on. I’ve only been doing this as a hobby for a little more than a decade. There’s still much to learn.

One thing I have learned, however, is the method I am approaching my basketball coaching translates very well to working in the shop. By taking the time to learn the proper fundamentals of different aspects of woodworking, you can more easily master the advanced techniques.

Think about it for a moment. What do hand cutting tenons and dovetails have in common? Besides the fact that it involves using a saw and not plugging in a tool, the main skills you must master are marking an accurate line and cutting exactly to it. Yes, seriously. That’s exactly what is required to make the joints sound.

So, how do you get that kind of experience? The answer lies in the punchline to a classic joke tied to New York City. A young lady gets into a taxi cab and asks the driver, “How do I get to Carnegie Hall?” The cabbie looks over his shoulder and cracks back, “Practice, kid.”

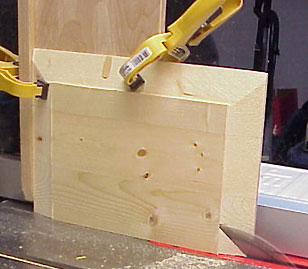

To get that kind of practice, you should line up a few practice boards of some inexpensive material – poplar, alder, red oak or the like. Mark a depth line and grab your saw. See how many dead perpendicular lines you can cut across the width of the board. When you fill one board’s width, cut that end off and start over. Look at the results. Focus on your grip and the flow of motion in your arm. Look at the results and evaluate your progress.

Do this five or ten minutes every time you go into your shop, and you will hone those skills to the point where cutting advanced joinery will be a piece of cake.

The same can be done for any number of other essential woodworking skills. Learning how to use your planes. Learning how to sharpen your blades. Learning how to properly work a router. Making high quality rip cuts.

Will it be fun? Maybe not. After all, our shop time is precious, and we want to spend all of that available time building projects. But, just as the kids on my team may want to play like LeBron James or Michael Jordan and shoot the lights out, they have to start by learning to do the essential skills properly. Once the are competent with those basics, the other stuff will start to come more naturally…

After that, hey, the sky is truly the limit.

Look around at the furniture you come in contact with every day, and you’ll see them there. Some have transitions in their profiles that add shadow lines, yet others are soft and rounded, easy on the eyes. Raised panels just staring at you, adding visual dimension to plain, everyday items.

Look around at the furniture you come in contact with every day, and you’ll see them there. Some have transitions in their profiles that add shadow lines, yet others are soft and rounded, easy on the eyes. Raised panels just staring at you, adding visual dimension to plain, everyday items.