So, you are visiting Tom’s Workbench looking for this week’s quick poll…

But, you aren’t going to see one here today on Father’s Day. Sorry ’bout that… you can count on one for tomorrow.

Instead, I want to focus on a very special woodworker who gave me the inspiration to get involved in woodworking in the first place – my dad.

He is the youngest son in a family of seven children and he grew up in an Italian American neighborhood in Fairview, New Jersey. Taught the value of hard work from a very young age, he worked to help support the family while in school. And, as soon as he was old enough, he enlisted in the United States Marine Corps, serving during the presidency of John F. Kennedy and the Cuban Missile Crisis.

After his honorable discharge, he married my mom and started work delivering soda – first with Seven Up and later with Coca Cola. Talk about grueling work… dad would deliver hundreds of cases of soda in the rain, snow, heat and cold for more than 40 years. I never liked helping him deliver soda… the times I did go out, it was back breaking work. Hauling cases up and down stairs at small convenience stores and eateries. But, my dad never stopped smiling or engaging folks in conversation. Even on tough days. Just a genuinely nice guy.

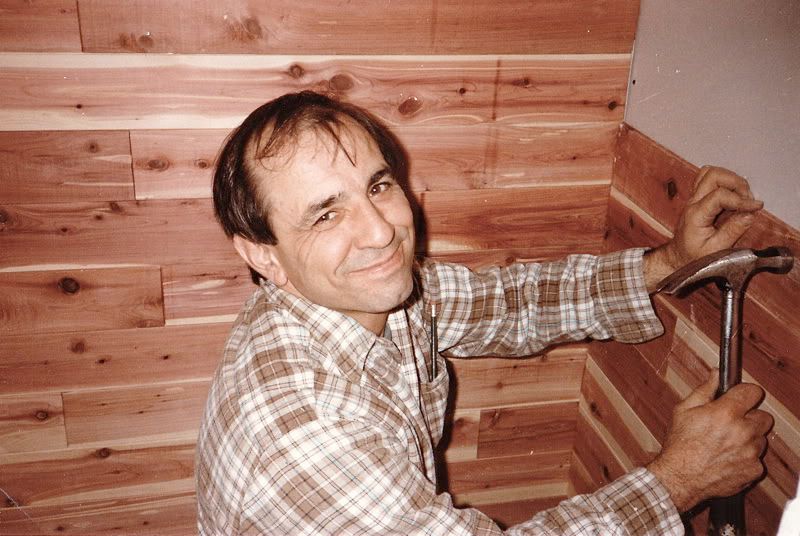

Always industrious, he worked hard to make his home a nicer place to live. After my parents bought an older home in Ridgefield Park, New Jersey, with the help of several relatives, he renovated the two family structure to get ready to start his family. Demolition, studding, electric, plumbing, drywall… the guy knew how to do it, or learned quickly. After the renovations, the house looked pretty darned good.

Years later, we moved further west into New Jersey to a town called Bloomingdale. It was a modestly-sized home that served our family well – when we were just little kids. But, as my brothers and I got older – and bigger – we needed more room to spread out. That’s when mom and dad came up with the idea of finishing our home’s basement.

I can still remember the planning phase… wondering why we didn’t just hire a professional to knock the job out and be done with it. That’s where dad’s wisdom and encouragement really shone. As the materials started arriving at the house for the renovation, he called his sons together and we watched this new show on PBS. It was called This Old House, and featured two bearded guys with New England accents finishing – of all things – a basement! We watched, while dad kept telling us, “We can do better than these two guys!”

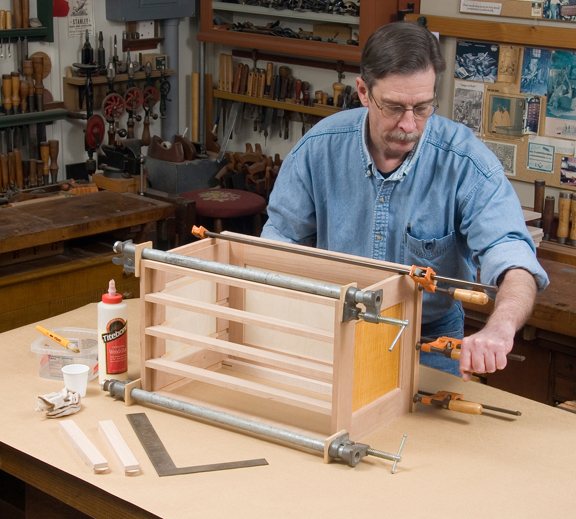

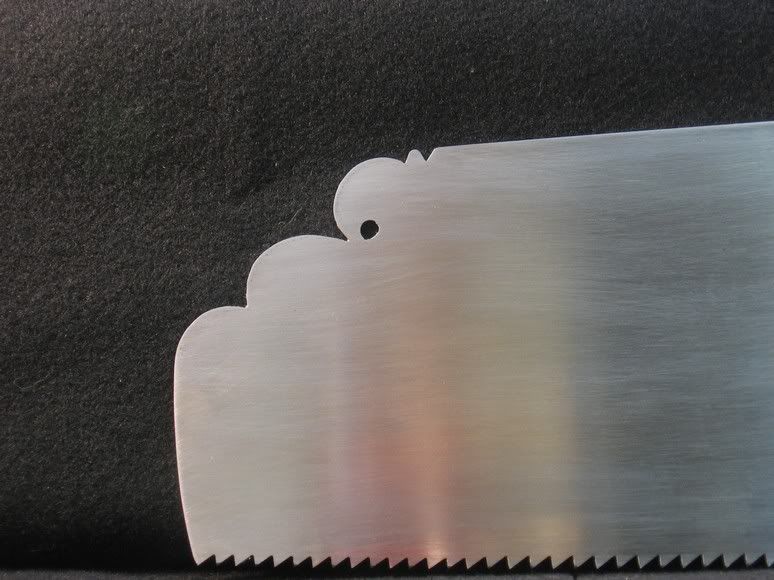

That’s when we hit it. Sure, the basement renovation took longer than six half-hour shows, but it was far more rewarding than anything else I had done to that point. My dad likes to take the time to explain stuff to a very fine detail. In fact, he’s the kind of a guy if you ask him what time it is, he will tell you all about the history of clocks and exactly how to build one. During the basement build, he showed me how to accurately mark wood for cutting, how to lay out stud spacing, when to nail and when screws are better… all the way to how to properly trim out the paneling to make the final project look sweet.

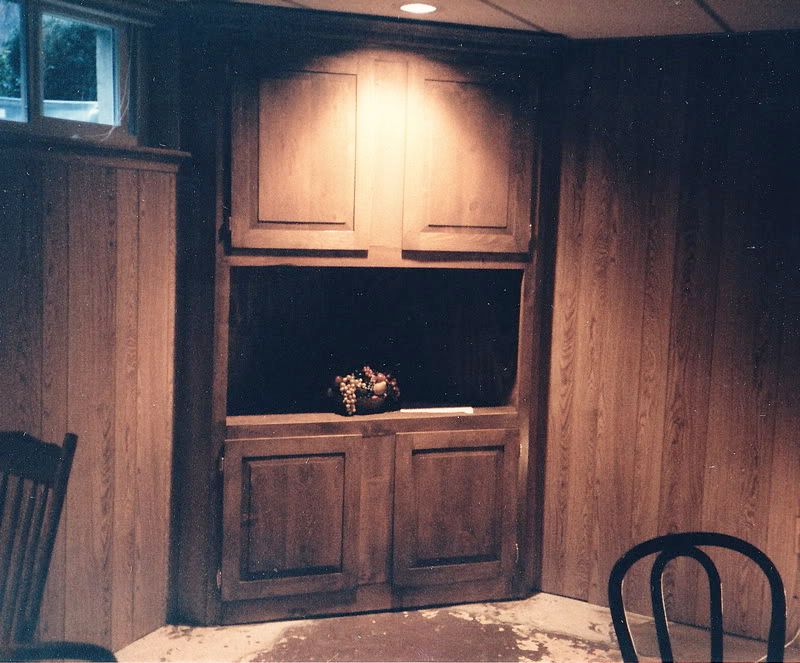

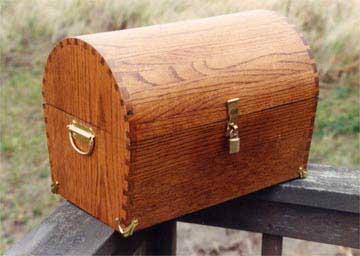

When faced with a challenging corner in the basement, he designed and built a corner entertainment center… much like the one I had built about eight years ago in my house. Just a clever idea to use a corner that would otherwise go to waste.

It’s funny how much what I learned during that basement renovation has helped me. In college, I was asked to be the guy who built the room divider that allowed us to use the dining room in my apartment as a second bedroom. Other people have asked me to come in and help with other construction projects in their homes and yards.

My dad has since retired from delivering Coca Cola. But, he’s not the kind of guy who likes to sit around. Today, he works as the maintenance guy at Glen Wild Lake, the gorgeous lake that his new house overlooks. This can involve negotiating with fish hatcheries to get the lake stocked with bass and trout all the way to coordinating the lowering of the lake level to get extensive dock work done.

The one thing that hasn’t changed is his interest in teaching. He takes the time to teach my sons and my nephews about everything… history, sports … and woodworking.

Thanks, dad. I doubt I would have come this far in life without your teaching, inspiration and encouragement.

Happy Father’s Day to you and all of the other dads out there.