I’m always amazed when I go to a specialty coffee shop. Not only is there a bewildering array of beans grown and harvested from areas around the world, there are also numerous levels of roasting that have been put on them to create a different cup of coffee. How about a light roast from Kenya, or a darker roast from Hawaii? And, once I make my choice, the questions keep coming at me… How do I want it ground? For a drip machine? A French press? Espresso? At this point, I’m usually looking for someone to just hand me a steaming cup of Joe and send me on my way.

When it comes to sharpening, the question of grinding comes back into play. Flat or hollow ground that is. And, depending on how you sharpen, you will come to understand and appreciate the difference.

Let’s start at the beginning, shall we? When a woodworker sharpens a chisel or plane iron, you are looking to get an edge where two faces of the tool intersect with zero radius. One face is the flat back of the tool. That’s why it’s critical to get the back of a chisel or plane iron flat and smooth, so it will intersect with the other side as cleanly as possible.

That other side, of course, is known as the bevel. Depending on the purpose of the chisel or plane iron, that can be any one of a number of angles. For most bench chisels, that is somewhere about 25 degrees.

Now, there are two different ways a factory – or a woodworker in his or her shop – can get a bevel into that shape. That can be done first on a flat sharpening medium. In that case, the bevel rubs against a flat surface, grinding away steel from the bevel from tip to heel. This is how people who use stones or flat-platen grinding setups create their bevels. Some experts say that because this is a tough way to sharpen and hone an edge, because at every phase of the sharpening process, you are abrading the entire bevel, a relatively large area to grind.

To help make restoring the tip of the bevel an easier task, many people who flat grind will take a few passes with the tool tipped to a slightly higher angle. What this does is polish just the tip of the tool, creating a very narrow band of honed steel at the end. This is known as a microbevel, and it can make keeping your tool sharp easier if you are going on the flat.

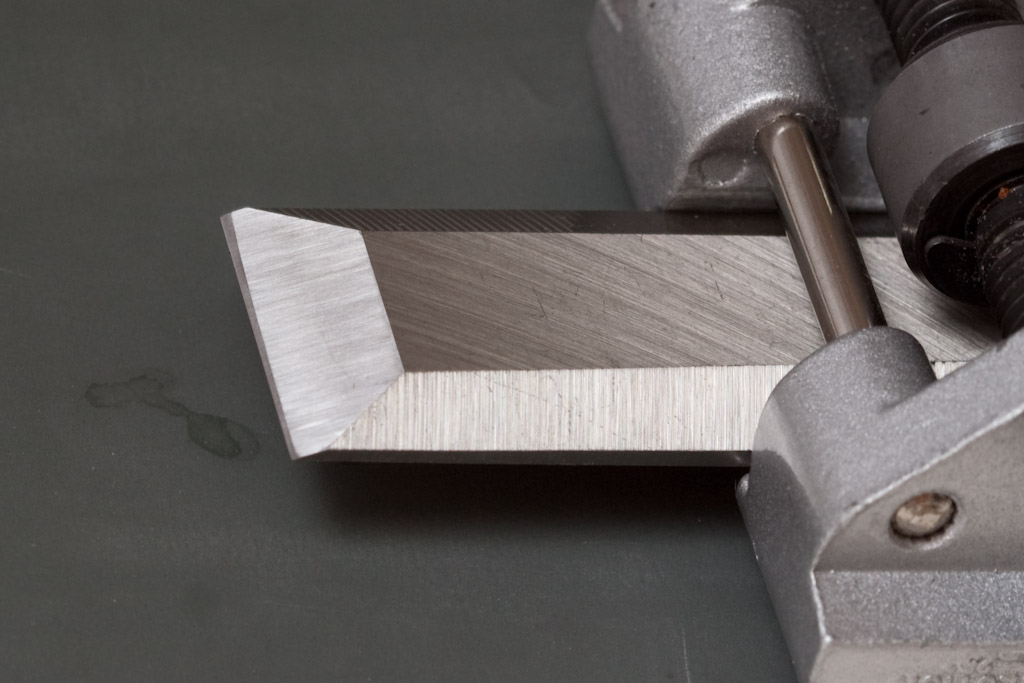

Now, if you are using a wheel to grind your bevels, you are looking at a hollow ground. When I’m working with a tool at my Tormek, The bevel of the tool is rubbing against the surface of a large-diameter wet grinding wheel. As the bevel touches the stone, it’s working against a rounded surface, which means if I have my guide set properly, the middle of the bevel is going to make contact with the stone first. In order for me to grind the bevel from tip to heel, I have to remove more steel from the middle of the bevel. This means that the bevel is being ground into a slightly concave shape. Remember, we’re not talking about a huge curve here… the surface of the bevel is relatively small compared to the diameter of the wheel.

This hollow ground, though, provides an interesting effect should you want to hone the tool on a flat medium later. As you sharpen the bevel, it will make contact on both the heel and the toe, removing material in two bands. This effectively reduces the amount of contact with the sharpening medium, making for easier honing later.

Are microbevels or additional flat honing required? Nope. A sharp edge will slice wood beautifully.

Which leaves more time to take a break and sit down with a nice cup of coffee.